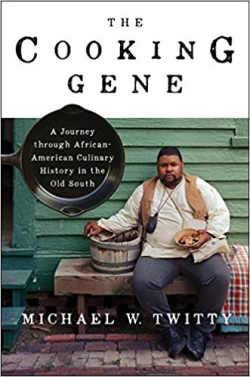

If Michael W. Twitty’s The Cooking Gene doesn’t win the 2017 Pulitzer Prize, there’s something very wrong with the committee.

If Michael W. Twitty’s The Cooking Gene doesn’t win the 2017 Pulitzer Prize, there’s something very wrong with the committee.

Then again, there always has been something wrong with America, as Twitty details with a righteous anger both searing and enlightening. This heavily researched “cookbook” (there are some recipes in it) is Twitty’s effort to unravel his past, a difficult task for any African-American.

All this gets explained, with the kind of writing that you want to linger over. But it’s hard to, as when he describes in detail how slave auctions worked, through the eyes of his own relatives, and why most African-Americans are part-white, through the eyes of those who were raped, sold, and brutalized in ways large and small over centuries.

Yet through it all, the food shines through. This is the book’s deeper meaning. Southern culture is distinct from northern culture because it’s African at its heart. What we eat, the ingredients we use, our spicing and love of the land, it all comes to us from Twitty’s people. Every southern white man, no matter how white he may claim to be, has African languages, attitudes, and ways of living deep in his heart.

Twitty’s search was made possible by both DNA science and a host of people who have made it their life’s work to tease out the past lives of black Americans through painstaking archeological work as well as hints given in old newspapers, court records, letters, and ads for slave auctions. Portuguese traders bought blacks from black princes, whom they treated as equals. Later waves were simply seized from lands where cash crops like rice were cultivated, and still later waves were seized merely as bodies to work the growing cotton fields as they drifted west. Along the way black men and women brought us barbecue, bourbon, burgoo, pepper sauce and jollof rice, which became a host of different dishes including jambalaya. Among other things.

Through scholarship, and through cooking, Twitty puts real names, faces, and suffering on enslavement. These men and women had names. They had families. They were torn from them forcefully, first in Africa, and later here in America, as the needs of “King Cotton” depopulated the tobacco lands of Virginia for the alluvial soils of Mississippi and Louisiana. This was the heart of the 19th century trade which finally precipitated the Civil War. Twitty’s great-great-grandfather, it turns out, was Richard H. Bellamy, immortalized for his Confederate service on a plaque in Vicksburg, and by the time Twitty is through you’ll want to spit on Bellamy’s grave too.

Tobacco became profitable because Africans understood its complex cultivation, and could be forced to give their secrets to white men. The same with rice. The same with other staples of the southern table. The same with just about everything we deem “southern culture,” our music and our attitudes. The blessing here is that the remnants, the recipes, the flavors, the tables set by black folks for the pleasure of whites, is what unites southern Americans today.

In the age of Trump all this becomes newly relevant. The rise of outright racists like Roy Moore, Jeff Sessions, and their demon spawn in Charlottesville attests to the fact that the Civil War is still going on, and that it can still be lost.

Right now, as this is written, it is being lost. In some ways 2017 is 1861 all over again, except northern states like Wisconsin and Ohio and Indiana have been lost to the evil heart of bigotry. In some ways 2017 is 1942 all over again, when our grandfathers watched Germany and Japan roll over Pacific Islands, northern Africa and eastern Europe into Ukraine.

I should add here a note about how I came upon this masterwork. We were visiting our son in Minnesota, bringing our “extra” car to him for his second year of graduate school. He was busy, so we limped toward a downtown brewpub, and on the way happened upon a small bookstore. I found a hard cover copy, full price, and decided that, being on vacation, I would treat myself and have something to talk about over pub grub.

Little did I realize just how much my life was about to change. All I can suggest at the end of this is that you, too, open yourself up to this change, and a new appreciation of your own history, no matter where your ancestors come from. (I am the first in my line to live south of the Mason-Dixon line, as if that matters.)

The story of Michael Twitty is the story of America, and in the end The Cooking Gene is a story of triumph. If you don’t believe me, just open your larder.