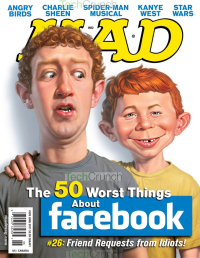

Mark Zuckerberg thought he had billions of friends. He was wrong.

That’s one of the clear lessons of the Facebook scandal.

The way competitors, celebrities and the media are piling on Facebook is something to behold. I said they were vulnerable to something like this at the start of the month. I was right.

Facebook is uniquely vulnerable because it has no customers. It doesn’t sell anything to people. Amazon sells stuff to people, and so when Trump goes after Amazon, Jeff Bezos sees his customers defending him. The same thing is true of Apple, which is why Tim Cook didn’t hold back on attacking the heart of the Facebook business model when given the chance on MSNBC.

Microsoft and Google have (so far) kept quiet about Facebook’s troubles, and for the same reason. Both run services supported by advertising. Microsoft has been backing away from this throughout the century (the MS on MSNBC is like the Cheshire Cat’s smile as it disappears). Google has been trying to diversify into products and autonomous cars. But their dependence still exists.

There’s one more important point to make about all this.

TV and cable stations now face to the same problem. They exist partly on advertising, but also partly on subscriber fees from cable operators, which guarantee them access to an audience. Their base businesses are slowly circling the drain, as more people “cut the cord” and move to “free” services on the Internet for their entertainment. Thus, cable talent is not averse to piling-on, and this is bipartisan.

Let’s just, for a moment, put aside Jim Cramer’s comparisons between Facebook and past “breach of trust” stories, whether they’re about payments or burritos. Focus instead on how Facebook can, and should be defending itself during this crisis.

They do it by defending the Free Web.

This is a battle Facebook has been fighting for five years. Its proposal, called Internet.org, has had a variety of modalities, everything from satellites to balloons, but the plan has always been to deliver a version of Facebook, and other free Internet services, to the developing world.

I’ve been tracking this story for over a decade. It started with village women buying flip phones, then going around to people in their villages selling text and phone services. The rise, and mass market for, smartphones has accelerated this change, and solar energy has helped. Solar can power both base stations and phones, cheaply. It means the most remote village is suddenly in touch with the world’s markets, and can talk back to them.

The best example of this power in the marketplace was the Zimbabwean rush to Bitcoin, which hastened the departure of dictator Robert Mugabe. This was a completely bottom-up, market-driven phenomenon. The Venezuelan effort to create a cryptocurrency around its oil assets is certain to fail because it’s top-down.

If I can be considered an acolyte of any economist who has ever lived, I think it would have to be Will Rogers. Yes, that Will Rogers. I wrote about him back in January. He was talking about money, but the same applies to bits:

Give it to the people at the bottom and the people at the top will have it before night, anyhow. But it will at least have passed through the poor fellow’s hands.

This needs to be at the heart of Zuckerberg’s counter-argument. Change the subject from “you are the product” to “we’re defending the Free Web.” It’s advertising that allows for free content in the West, and free access in the East. The purpose of collecting data on users is to sell advertising that more closely meets their needs, just as tech magazines 30 years ago would be filled with blow-in cards demanding data in exchange for subscriptions.

Change the subject. Get on firm ground. Without advertising, the only “free” Internet becomes information with an agenda. Talk darkly about government agendas, and then bring up the political agendas of those who abused Facebook in the run-up to the 2016 elections.

Only after that do you apologize. You can also act. You can refuse to do business with politicians or political action committees or any company that works for them. You can restrict access to user data. You can do a lot of things.

But you don’t start winning the argument until you get on solid ground. The Free Web is that solid ground.

Facebook has hundreds of millions of users.

And Facebook has thousands of customers: the businesses and governments that pay good money to Facebook for access to the data generated by Facebook’s users. Facebook sells this user data to its real customers.

Facebook has hundreds of millions of users.

And Facebook has thousands of customers: the businesses and governments that pay good money to Facebook for access to the data generated by Facebook’s users. Facebook sells this user data to its real customers.

Facebook is not supposed to sell “data,” but ads.

If the placement of ads is informed by data, it means Facebook ads are trying to provide you a service, delivering ads to you that you might be interested in.

Selling data is a line that should have never been crossed, except as gross reports. Magazines have always been able to compile this kind of data on readers. Newspapers too. But when you sell Personally Identifiable Information, that’s different.

There are two differences between Facebook ads and magazine ads. First, Facebook ads are much cheaper, on a cost per thousand basis. Second, Facebook ads can be narrowly targeted, because of the huge user base. You could get 10,000 left-handed bassoonists, for instance, or 100,000 fans of Pearl Jam who also own dogs.

What Facebook did was more insidious. First, it allowed political groups to collect data through its system who should not have been allowed to do so. Second, it apparently dealt in personally identifiable information, a gross privacy violation.

At its heart, the Facebook business model is presented as no more harmful than a magazine that makes you fill out a blow-in card to get a free subscription, only without the card.

To the extent they did more than that, they deserve what they get.

Facebook is not supposed to sell “data,” but ads.

If the placement of ads is informed by data, it means Facebook ads are trying to provide you a service, delivering ads to you that you might be interested in.

Selling data is a line that should have never been crossed, except as gross reports. Magazines have always been able to compile this kind of data on readers. Newspapers too. But when you sell Personally Identifiable Information, that’s different.

There are two differences between Facebook ads and magazine ads. First, Facebook ads are much cheaper, on a cost per thousand basis. Second, Facebook ads can be narrowly targeted, because of the huge user base. You could get 10,000 left-handed bassoonists, for instance, or 100,000 fans of Pearl Jam who also own dogs.

What Facebook did was more insidious. First, it allowed political groups to collect data through its system who should not have been allowed to do so. Second, it apparently dealt in personally identifiable information, a gross privacy violation.

At its heart, the Facebook business model is presented as no more harmful than a magazine that makes you fill out a blow-in card to get a free subscription, only without the card.

To the extent they did more than that, they deserve what they get.