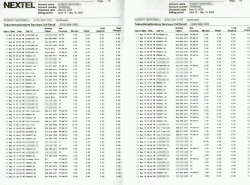

The service was a phone call. The data was the time, duration and number called. The data was used to generate a bill for service. AT&T still mails customers this data.

There was also another layer of data, hidden beneath the services data, namely the content of the call. This was only available to law enforcement, with a warrant. A number might be tapped or (when technology permitted) a subject might have all the numbers they used tapped. This data was secured. It could only be used in criminal investigations. Civil cases could be tossed if this data were misused.

In print, there were similar splits between service and data. Editorial was the service. Subscriber lists were the data.

The mailing list industry grew out of this data, mixing and matching subscriber databases to get a rough profile of prospects. Politicians also used these lists to fundraise, and to target mailings. In bulk, the data proved the publisher was hitting its target, that an advertiser would reach certain people, in certain quantities, if they bought a billboard along the editorial road. The lists were a huge profit center.

There was also a strict “service” and “data” separation between what the publication was doing editorially and what its ad department was doing. Editorial was supposed to speak “for the readers.” Successful editors, and publishers, had a sixth sense about what their target market wanted to know, and how to give it to them. The content, and its production, were more closely protected by the First Amendment than advertising was. Editorial and marketing workers were separated by a so-called “Chinese Wall,” semi-permeable. Publishers could berate writers, or demand specific stories, within ethical bounds defined by the publishers and their markets.

Mix all this data and service together in one big glop and you get Facebook.

On the Internet, all types of data that used to be separate become available to the marketer. (Advertisers buy advertising, marketers create strategies to sell stuff.) The old First Amendment limits defining “commercial speech” as distinct from “editorial speech” disappear.

Because the print ad models are gone, advertising and editorial become jumbled. Regulation of “political advertising” isn’t enough. If profile data is used to generate editorial content, the victims can be waterboarded with more and dragged down whatever rathole a politician wishes to drag them down. This is the Trump business model, and it’s not just pursued by Cambridge Analytica, but by Breitbart, by Fox, and by Sinclair. It’s the business model of fascism.

The “chinese wall” is gone. The separation of editorial and advertising is gone. The “Fairness Doctrine” that used to protect people from propaganda is gone. Likewise, the ability of third parties to produce content you might find interesting, and profit from it, is nearly gone.

The end of this split between data and service impacts all types of content providers. Musicians as well as writers can’t get paid for their work.

Here’s today’s big news.

That is, unless something stops them.

This is the nightmare we call the “Free Web,” but those now demanding that people pay for every piece of content they see are already being brought up short. In terms of the public interest, such an approach is a disaster.

Anyone with a paywall has a newsletter, becoming not a mass medium but a class medium, available only to those willing to pony up for that piece of content. This makes people even less likely to exit their silos, their narrow interests and views, because they can’t afford to. If the only content your conservative friend can access free comes from Breitbart and Sinclair, how are you ever going to wake them up?

How many newspapers and magazines does the average household buy? It depends on the household, but increasingly the number is zero. The median family income in the U.S. is still under $60,000. Take out rent, the car, food, the absolute necessities, and there’s very little left for content. Maybe you’ll buy a Netflix subscription, but increasingly you’re cutting the cord on your cable because you can’t afford it. What happens when the Internet adopts the cable business model, as it’s doing with “TV Everywhere,” forcing people to buy bundles of content with their Internet subscriptions? What else can they afford then?

What happens is the lights start going out all over the world. While chiding Mark Zuckerberg for what happened in 2016, we also need to keep our eye on the ball and protect the free web. Without compelling new business models based on the content we’re seeing, not just the data used to find it, the free web doesn’t stand a chance.

Our political problems, in the end, are a business model problem.