The Greatest Progressive of American history was J.P. Morgan. But he wouldn’t be one today.

The Greatest Progressive of American history was J.P. Morgan. But he wouldn’t be one today.

Let me explain.

Businesses have always talked up the idea of progress, of change. It’s at the heart of the progressive idea, a constant, incremental improvement. Progressives believe in things getting better, and the way they usually get better is by something better coming along. Better products, better services, and better ways of doing things. Today these are all byproducts of competition.

They weren’t always.

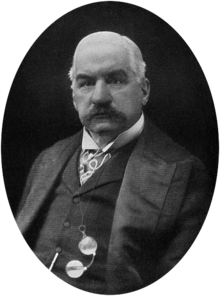

Morgan was active from the Civil War through the first decade of the 20th century. He is usually portrayed as either a colossus or an octopus. He was the man behind the “trusts.” Trusts were evil. He was Teddy Roosevelt’s great nemesis.

But was he? We know the men were close. Morgan and Roosevelt were both Republicans.

What is undeniably true is that, during Morgan’s time, America and the world were short on capital and on basic infrastructure. We couldn’t afford to have several rail lines serving the same point, or several telegraph wires serving the same office. That would mean other points and other offices got no service.

John D. Rockefeller drove people like Ida Tarbell’s father out of the oil business. But what were those small oilmen doing? They were cutting into one another’s claims, loading oil into wooden barrels, they were refining it in small pots, they were killing horses and making the roads of western Pennsylvania quagmires. They were, literally, killing one another. Oil is hard enough. It’s naturally polluting, in every step of its production. Competition made things worse.

Instead, Rockefeller built huge refineries. He built pipelines to get crude across mountain ranges without spilling half of it. He managed oil fields for maximum, sustained production, instead of pulling everything he could get out today and bugger all tomorrow. Rockefeller made oil dependable. He also made it so cheap that gasoline and asphalt, which had been “lost fractions” at the start of his career, could be sold to the auto business as cheap solutions to the transportation problem.

Well run businesses limited waste, brought people out of poverty, and made a profit for small investors. Progressivism created the middle class. “The Uneeda biscuit in the airtight sanitary wrapper made the cracker barrel obsolete,” as Prof. Harold Hill sang in The Music Man.

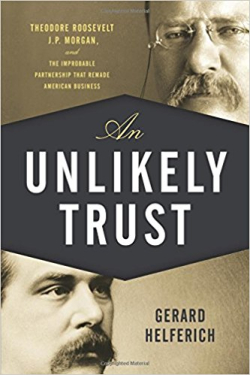

What was needed for stability was a deal to be made with government. Morgan made it, with Teddy Roosevelt. (The cover of a book about that is to the right.) Government could compete directly with business to regulate profits, even setting standards, and in exchange scaled businesses would control key markets.

The result was the modern city.

Our road networks, our transit systems, our electric and phone utilities, our natural gas distribution, all our urban infrastructure dates from the Progressive Era. I live in the same house, along the same street, as people did 100 years ago. Progressivism transformed America by creating the structure of our cities and allowing manufacturers to know the costs of essential industrial inputs, so they could scale effectively.

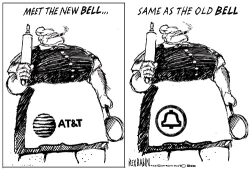

Morgan was a progressive, however, only in the context of his time. Once built the great utilities – gas, transit, electricity and telephony — are no longer cutting edge. Once society scaled manufacturers needed competitors to propel change forward. The Morgan city created tons of capital, which nurtured this competition, but supply also needs demand or you don’t have a market.

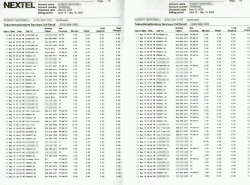

Meanwhile, once established, monopolies like AT&T became risk-averse. They demanded their profits up-front and put those profits into their pockets. The tech era has been all about risk-taking, and those who took the biggest risks have reaped the greatest rewards. AT&T has been rendered obsolete.

The needs of business are different from the desires of businessmen. What business needs today isn’t capital, but opportunities. Just as the supply of goods overran demand in the 1920s, resulting in deflation, so the supply of capital is overrunning what the market can demand today.

Business needed what Morgan offered at the end of the 19th century. We need a different deal today. Today money trickles up, the wants and needs of people creating demand, which attracts investment, which becomes the engine of economic change. The mass production needs the mass consumption, and consumption starts with money in your pocket.

Today, we have too much capital and not enough opportunity. Demand could create opportunity, but the “trickle down” theory keeps money in the hands of capital, where it’s vulnerable to bubbles and scams like Bitcoin. Bubbles destroy value. They also destroy savings. Demand gives capital something to do. If J.P. Morgan were around today, he would be a Democrat. JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon is one.

The point is you can’t make progress without dealing with what business needs, and what business needs (as opposed to what it wants) changes over time.

Doing what’s needed for growth has always been the genius of America. We figure it out and find a way to deal with it. We are a Hamiltonian nation. ( $10 bill from https://en.wikinews.org/w/index.php?curid=23022)That’s our nougaty center. The Jeffersonian rhetoric is just the thin chocolate coating.

By the standards of our time, Morgan is a villain. By the standards of his own, he was a hero.