Almost a decade ago, I dedicated a week of this blog to the story of Bruce Springsteen.

Almost a decade ago, I dedicated a week of this blog to the story of Bruce Springsteen.

I told the tale of a musician called to public service by the horrible events of 9/11 and recounted how he told America’s story through his music during that decade.

Today I want to tell a different, more private story. It’s a story of redemption and triumph, through the power of love, starting with the bitter acceptance of loving yourself.

It’s the story of Jason Isbell

When I wrote my Springsteen story, Isbell was a mess. As he admits. In 2009 he was a 31 year-old guitarist and singer for the Drive-By Truckers, a southern rock band in the tradition of Lynyrd Skynyrd based in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, near Huntsville.

Skynyrd, I should note, is not my thing. Neither, at the time, were the Truckers. I had never heard of Isbell.

I first heard of him a year after what he might call his “conversion,” on Mark Maron’s WTF Podcast. Maron had run out of comics to talk with, he was on something of a roll after a New York Times profile, and the call went out for musicians. DBT lead Patterson Hood took Maron through the Truckers’ story, and it was intriguing, because they weren’t a bunch of ignorant hippie kickers out to recapture rock for God’s own people. Quite the opposite. They were a bunch of serious, middle-aged musicians, second generation rockers really, and family men. Such is the duality of the southern thing, as Hood wrote.

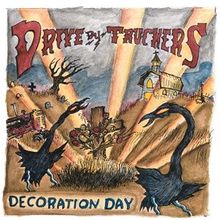

Isbell was the “genius boy” always hanging around the studio, who they brought into the group to liven things up. Which he did. He also partied. Hard. Drink and drugs and wild, wild women. The whole lifestyle. The boy was too much for the good men of the Truckers, and despite their financial success with him, including the title track to 2003’s Decoration Day he was out.

The firing was where our story begins.

I wasn’t alone.

At the end of their talk, Maron picked up two microphones and Isbell sang a song from the album. It was Elephant. I cried then, and soon had need of it, as my mother began dying from dementia, in California. Like the subject of Elephant, Tillie was surrounded by a family that was sorry she was dying alone. I could only get there twice a year. The song’s narrator sang his female cancer victim a Harry Nilsson song (in the original lyric). He picked up the hair that fell from her head, he carried her to bed, he “buried her a thousand times.” But one thing remained crystal. “No one dies with dignity, we just try to ignore the elephant somehow.”

For those engaged in grieving, or pre-grieving, it was cathartic and welcome.

What was amazing to me, after I picked myself up off the floor, was just how many classics Southeastern would contain. Some, like Elephant and Yvette, were told in the third person. Some were more personal, like Cover Me Up and Stockholm, which describes the city but also compares love to a kidnapping. The album finished with Relatively Easy, which starts as a story but ends up personal and self-deprecating. “Our kind has had it relatively easy.”

His lyrics are pure poetry, every one of them. You can pull them apart, discovering a world of constant surprise, then put them back together and tap your foot to just about any of them. (His tweets are also damned funny.)

As I watched the world discovered Jason Isbell. Dismissed as an “Americana” artist by the country music establishment after Southeastern, he was given a residency at the Country Music Hall of Fame last year after The Nashville Sound, which told said country music establishment what they could do with their right-wing politics and made them like it.

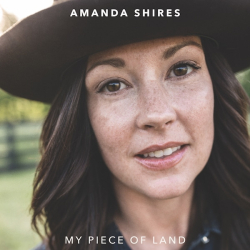

Isbell has also proven to be a great role model. The woman who helped save him, Amanda Shires, is now Mrs. Isbell, and they have a little girl. He has been at the forefront of bringing new artists, especially women, to the genre. He has given Amanda’s lyrics more gravity and in turn she gave his work more depth. I especially like her CD The Way It Dimmed, from My Piece of Land, about “the fire, and the way it dimmed, as a fire will sometimes do.” It’s a beautiful song about becoming comfortable in love, which is more difficult than falling in love and far more worthwhile.

The best song on The Nashville Sound is the Grammy-winning When we were Vampires, about marriage and death, how time runs out for all of us and how that might be a blessing.

But I want to close with the album’s last piece, something he wrote for his daughter. It’s a remembrance of childhood called Something to Love, and contains the very best career advice I’ve ever found:

I hope you find something to love

Something to do when you feel like giving up

A song to sing, or a tale to tell

Something to love, it’ll serve you well.

This sums up my own life. I’m not rich, I’m not famous, but for 55 years I’ve been a writer, saying what I feel for anyone who will listen.

It’s enough. Finding something to love will indeed serve you well.