It was for the son of one of her co-workers. The groom was born here, the parents arriving from India a few years before his birth. The bride was born in China but moved here as a toddler and is a U.S. citizen.

The bride and groom grew up together. They met in high school about 15 years ago. They moved among their guests with the grace and comfort of a long-married couple, secure in themselves. Their relationship may have once been controversial, but their joy in each other buried that long-ago. They live in Boston. He is a doctor. She’s a business consultant. They came down to be with his family. Some of her relatives traveled from China to Georgia to be at the celebration, in the shadow of Stone Mountain’s Confederate carving. Some of his traveled all the way from India.

Then the bride’s father spoke. He talked about the union of two old civilizations, India and China, taking place in the world’s youngest civilization, America. It, too, was very moving.

Later, everyone danced, and a woman in traditional Chinese garb raised her hands to Indian disco, alongside her new relatives.

I thought about what the couple’s children will be called.

They’ll be called Americans.

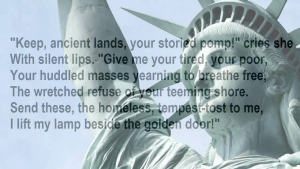

This is the miracle of our country, something Trump can’t take away. It is our secret sauce. Emma Lazarus’ words won’t be erased – “Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me. I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

Unless there’s a black woman somewhere. Because the name Dana, a Polish word for a Danish immigrant, came into vogue around my African-American neighbors in the 1960s. Most people named Dana are now female. Queen Latifah is a Dana. I have met several black female Danas here in Atlanta. One grew up on my street and wrote her name in flowing letters on her mailbox. Maybe, someday, one of these Danas will marry a German, or an American, who shares my last name. Until then, I stand alone.

Later, after learning the Blankenhorn story, I talked about how during World War I, German-Americans began calling themselves just Americans and, how, after World War II, most Germans started calling themselves just Europeans.

Like the Trumps, after a few generations white Americans are just Americans. We can get away with that. So, too, third-generation Asian-Americans, like a college classmate whose first name was Asuka, which we all pronounced “Oscar.”

My black neighbors are exceptions, and it’s not right. Even Tiger Woods, one-half Thai, is still considered African-American. Why isn’t Charlize Theron African-American, then? The current civil war is aimed as much at native-born black Americans as Mexican-American or Muslim immigrants. If the groom’s family, at this wedding, had been Muslims in India – they weren’t – you still couldn’t tell them apart from any other Americans. Yet we would be told, by our political leaders, to hate and distrust them.

What we need to learn, all of us, is that we’re all just Americans. We need to stop looking at color, or heritage, or social class, and treat each other as we’d like to be treated.

That’s the victory this generation is fighting for.

One more thing.

During that wedding celebration, after several energetic Indian dances, the groom brought up one of his medical school classmates. He’d gone to the Morehouse School of Medicine, and the classmate was a true Morehouse man, ebony-colored, tall, wide and handsome, who had bought himself a blue Indian suit for the weekend and looked grand in it.

The guest handed the DJ his phone, with an instrumental on it. The DJ connected it to his sound system, and the Morehouse man began singing, a Motown song, in a glorious falsetto. It was a slow dance, a romantic ballad, so everyone began to slow dance – Indians, Chinese, white, black – Americans all.

Abraham Lincoln liked to repeat the story of the king who asked for a sentence that would be true in all types of circumstances, and was given the answer, “And this too shall pass away.”

Trump too will pass away. America will remain standing.