One way it’s being fought is through monuments.

Early in the 20th Century, groups of southerners seeking to glorify white supremacy and the “Lost Cause” built monuments in town squares around the country, including in DeKalb County, Georgia, where I live.

Stone Mountain is the largest such monument. There are many others. One sits in front of the old county courthouse in Decatur.

When these monuments are threatened, their supporters swarm, claiming they have nothing to do with treason, or white supremacy, but are simply meant to commemorate heroes and a part of American history.

It’s hard to fight them, on behalf of an empty town square.

It’s emotionally devastating.

I’m the first in my line, mother or father, to live in the South, and the horrors described are nothing less than a continuing Holocaust. I knew many survivors of Hitler’s terror growing up on Long Island, but the horrors shown by EJI were committed, and are still being committed, against black neighbors who transformed me from man-child to man. Rather than sentence violent racists to jail, they should be forced to go through that place, and then write about it.

He is mentioned by Aroine Irby, a black Air Force veteran from Selma, who guided our tour through the duality of the southern thing. The ghost of Lurleen’s husband haunts the ground , “a pawn in the fight against the Civil Rights cause,” as Patterson Hood wrote. “Fortunately for him, the devil is also a southerner.”

Alabama has paid a fearful price for George Wallace. Its population is now less than half that of Georgia’s, its economy an even smaller proportion. A half century after Dr. King’s death, what they’re proudest of at the “Confederate White House,” which sits just south of the Capitol, is that Alabama is now a low-wage colony for Korean car makers.

After some Thai ice cream across from the corner of Zelda and Fitzgerald Roads, I was ready for the real aim of my trip.

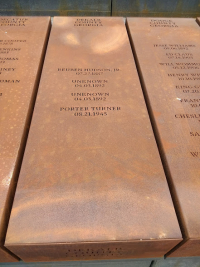

The Monument.

Then, at the top, you start walking down, and face hundreds of steel columns, shaped as coffins, held to the ceiling by poles which feel like ropes. Each carries the name of a state and county, along with the names and dates of documented lynching victims. You go from stone to stone in the darkened space, seeking your home county. The path angles down, which means the stones seem to rise. Soon, the stones are above your head, the space as dark and silent as a tomb. At eye level, now, are stories, of men, women and children, hung across the South for no reason save skin color, sometimes burned alive, surrounded by white men, and women, who paraded around them gleefully as at a picnic.

Finally, you think, it’s over, because you have reached the bottom of the space. An open door beckons.

The most recent date is 1945.

If you’re not crying now then you have no heart, nor soul. You deserve to be forgotten as George Wallace is.

There’s a debate going on in Decatur right now. About a Confederate monument by the old courthouse, erected midway in the Jim Crow era, commemorating those who fought and the cause they fought for.

Leave it. But consider doing what the Monument in Montgomery suggests. Consider taking the DeKalb County coffin, placing it opposite the Confederate monument and telling the full story.

This is your Monument

This is your Stone.

Do we have the strength to lift it

And the courage to bring it home?