When I moved to my present house in 1983, all views of the urban future were dystopian.

When I moved to my present house in 1983, all views of the urban future were dystopian.

Suburbs were the thing. Cities were being consigned to the scrap heap. Atlanta offered a three-bedroom Craftsman bungalow, built in 1923, a few hundred feet from a train station, and with the nicest neighbors you could want, for $49,500.

Today the house is worth over $500,000. We put a lot into it along the way. It’s bigger than it was. The kitchen is huge, with all-new appliances. All the utilities are upgraded. It’s air conditioned.

More important, views of the urban future have reversed. Now everyone loves density, and the city wants to turn the train station’s parking lot into “workforce housing” so people making under $100,000 can live here.

But the assumption that the urban future is golden today is as warped as the attitudes of 1983 were.

Those attitudes were premised on the idea that people would gladly “drive until they qualify.” They discounted the real costs of commuting – the time, the gas, most of all the aggravation. Super-commuting, in which you spend 3 hours getting to-and-from work each day, has caused a backlash, especially among young workers, many of whom don’t have the money to outfit a big house anyway, nor the patience to pursue a monoculture of grass every weekend.

Those attitudes were premised on the idea that people would gladly “drive until they qualify.” They discounted the real costs of commuting – the time, the gas, most of all the aggravation. Super-commuting, in which you spend 3 hours getting to-and-from work each day, has caused a backlash, especially among young workers, many of whom don’t have the money to outfit a big house anyway, nor the patience to pursue a monoculture of grass every weekend.

But there is a hidden trend among the super commuters. Increasingly, they’re combining transit modes, driving to train stations, for instance. This is precisely what Atlanta is trying to discourage by building on their transit lots.

One of my relatives recently talked about doing this. He lives in Corona, California. His job is in Pasadena. That’s a 90-minute drive, but it can be made livable by careful use of public transit. Drive to the transit station, take a train near the destination, then park a car there for the end of the trip.

Or you could Uber, I suggested.

Self-driving cars are usually shown as clones of current cars, only without the steering wheel. I suspect it will be 2025 before steering wheels disappear entirely, but when they do, cars will change completely.

Think about the inside of the car today. Banks of seats, all facing forward. Uh, why? If the car is driving itself, and you don’t have to pay constant attention to it, why are you looking outside at all? Why aren’t you using the same networking systems that make the self-driving car get you there to do other things? You could be reading a book, watching a movie, playing a game or (this is the important bit) you could still be at work.

When cars are self-driving, when you take back the attention you’re now paying to them, you’re no longer out of touch. You can continue that meeting, or that analysis, or that management function, that you were doing when you left.

Exactly. I’ve been telecommuting for 35 years, and it amazes me that the trend has been accompanied by rising density. The dominance of San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles and Washington over technology, money, entertainment and politics (respectively) has become ever more pronounced. Everyone who wants to be a player in those games must gravitate to those cities, at least while they’re playing the game. This makes car-sharing services cheaper than owning a car in these places.

When you no longer play the game, of course, you get out. It’s the mark of having “made it” in Hollywood that you don’t live anywhere near the place. Once power players no longer have power, they also go where they like. They build new lives in smaller cities, usually college towns, but also places with reputations for a high-quality lifestyle, like Asheville and Santa Fe.

The drive to get out when you make it is shared by many Silicon Valley companies. It’s why Apple is building in North Carolina and why Amazon wants an HQ2. Decentralizing cuts costs. It also spreads the political wealth – North Carolina and Georgia are purpling because San Franciscans and Los Angelenos are moving there.

You can commute from further away.

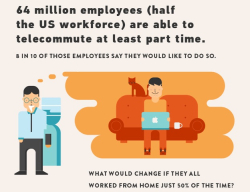

Suddenly, that two-hour “drive” to your dream home in the country isn’t a two-hour drive. A middle manager is no longer out of touch. My own wife likes to shorten her 75-minute mass transit commute by coming home early some days and taking late-afternoon meetings from her home office. She has also gotten permission to work twice each week from home.

There are going to remain people in the center. Poor people. Well, poorer people. Young workers who can’t afford to buy out of town. Older workers who prefer urban conveniences. They’ll remain a thing for some time.

But the trend is unmistakable. After a generation spent coming into town for an easier commute, high-income, and high-status people are going to start living further away as that commute becomes less onerous.

This will impact insurance rates. Self-driving cars are safer, so you’re going to have to pay extra if you want to control the car yourself. Middle-class commuters will find they save money switching to cars without steering wheels, just as they’re now seeing that they can save by switching to hybrid or electric cars.

All this will accelerate the market’s move to a self-driving future and hasten the other changes I’ve discussed here. When driving no longer costs attention, you will move further away. As people increasingly work from inside their cars, telecommuting will increase.

This marks the same kind of profound change on the city of my kids’ future as the move back into the cities marked on my working life.

Urban planners don’t know shit, and they never did.