A climax state, whether it’s a swamp filled in by peat, a redwood forest, or a planet filled with huge dinosaurs, is the most vulnerable thing in nature. It only looks stable. But a fire, or any sudden conflagration, can destroy it utterly. Mankind has, in the last thousand years, created such a climax state.

This was all described to me in the summer of 1991, when we took our family vacation around our home state of Georgia and found ourselves riding in a canoe through the Okefenokee swamp. Our guide described how the life-and-death competition among plants and animals leaves organic matter behind, which fills in the water and creates little islands, which are eventually connected as more water disappears. But these islands are highly flammable. A fire in the swamp clears them out, leaving a new swamp for creatures to compete in.

It's lack of competition that makes ecologies vulnerable.

In politics, this climax state is called autocracy. It’s a monopoly of power, held by a few who are dedicated to stability, and it is always followed by a civic conflagration – a war, an uprising, an economic collapse – that restores competition in the marketplace of ideas. America has succeeded until now because we have resisted this call to autocracy, whether from generals, billionaires, or religious leaders. Now it’s coming from the White House. Trump has brought autocracy to power, and we’re chafing under it, rightfully so.

Why is it that the people who benefit most from competition have forgotten these key lessons?

Technologists are also cyber-libertarians. Libertarians routinely ignore the climax state of business. Every market ever developed in this country consolidates into one or a few “winners,” who then seek monopoly rents to extend their power. We first saw this with oil and with railroads, in the 1880s, and it took a generation of progressive agitation, supported by business, to put that genie back in the bottle.

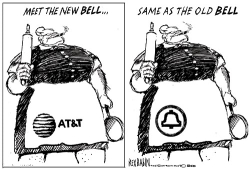

Until the 1950s, most monopolists remained under firm regulation. AT&T gave universal service in exchange for rate regulation. Movie theaters lost their studios when they began to squeeze them as TV rose to challenge them. IBM signed a consent decree covering its mainframe monopoly as early as 1956.

Today cable TV is considered to have a monopoly over Internet and TV service. But new technology broke every one of the earlier monopolies, and 5G technology will break this one too. There is also no guarantee that today’s cloud platforms will always be the dominant forces in our economy. It just seems that way.

Because technologists are cyber-libertarians they were also sanguine about fascism, an even greater threat. They failed to see a threat to themselves in this climax state of politics. A rigid political system, dedicated only to its own continuation, is anathema to change of any sort, even to technological change.

People with the ultimate power in technology, however, now seem alive to the threat. Tim Cook is gay. He’s alive to the threat. Marc Benioff is a Democrat. He’s alive to it. Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post. He’s alive to it. Google and Microsoft are led by Indian immigrants. They’re alive to it. Jack Dorsey is starting to pay the financial costs of maintaining ordered liberty on Twitter. He is becoming alive to it.

What technologists are learning, slowly, is that there is a difference between liberty and license. You are free to say or write what you want, but no one has an obligation to print or listen to it. The First Amendment only protects against government action, not private action. Which is a good thing.

The task before us right now is to overthrow fascism in our own country. Donald Trump is a racist, sexist, anti-semitic brute, a tool of the worst angels of our nature, who shouldn’t have gotten any closer to the White House than I am. But the cyber-libertarianism of the 1990s helped fuel his rise in the 2010s. Technologists forgot the difference between ordered liberty and absolute license, and foreign dictators took advantage.

But they could. By taking advantage of the stupidity of cyber-libertarians and the cupidity of liberals, fascists have risen among us, not just in the U.S. but around the world. They have created a war of all against all, and everyone is going to lose.

There are going to be many, many casualties over the next few years, both economic and real. A lot of investors who, like me, thought themselves well set for retirement are going to find themselves eating cat food, or worse.

That’s because, as with every other crisis of the 21st century, this is all a distraction from the biggest threat of all, climate change, the fever that continues to grow on planet Earth and threatens to throw off humanity like a virus.

In the lifetime of our children.