This should be obvious. Trump threw a party for his friends a year ago, but the $1.5 trillion bill must be paid.

That means interest rates are going up. Housing and autos are already tanking. Companies that want to borrow money are going to find it more expensive. The lucky ones might get the equivalent of adjustable rates, but those will adjust higher.

Meanwhile, private debts must also be paid. There’s a mountain of private equity debt out there, along with a mountain of student loan debt. There’s a global market of debt, much of which will be unpayable. Bad debts will have to be written off. Thanks to Obama, our banks will survive. I can’t say the same for Europe’s.

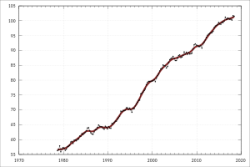

But there is good news. It’s the same good news as in the last two recessions. Productivity is about to leap ahead.

While a lot of people are going to lose their jobs, and some industries are going to virtually disappear, there’s a huge opportunity for those who take advantage of everything tech can do to lower costs, to eliminate labor, to make computers do more. The cloud czars fell hard, but they will come out of this stronger than ever.

The same thing happened during the Great Recession, only this time the victims included big box retailers that benefitted from the recession of the early 1990s. More important, insurance brokers, mortgage bankers, and loan officers who considered themselves the gatekeepers to the middle class, in suburbs and exurbs, were also blown out. It was this economic transformation, as much as anything else, which fueled the rebellion that led to Trump.

This is what productivity looks like. You get machines to do the work of people, and you need fewer people to do the same work. In the early years of the PC revolution, this efficiency meant managers could just do more. Now it means we don’t need the managers.

The process of change, expanding productivity and reducing headcount, goes on during periods of growth as well as decline, but it gets urgent during recessions. Companies are trying to survive, so they cut costs as much as they dare. Consumers are trying to survive, so they’re more willing to engage the market in different ways.

Customers go to where they perceive value. This is true for business customers as well as consumers.

Some of the biggest changes in the next recession will come in health care. A lot of people who think they have monopolies are going to find out they don’t. Insurers are buying or building their own facilities. Consumers are being pushed into these “managed care” plans, where care decisions might be between a patient and their doctor, but the doctor is a corporate employee who isn’t allowed to draw outside the lines.

In the late stage of a recovery, like the last two years, a lot of people have excuses for why certain actions are unthinkable. We distrust people with our data, and during good times we find all sorts of ways to keep it from people or to handle it inefficiently. The companies that use that data best are going to grow in the next few years, and those that either don’t collect it, or collect it and don’t use it, are going out of business.

Few people knew middle management would die after the 2000 recession, or that financial professions would die after 2008. There are no guarantees in any forecast. All I do know is that, based on history, productivity is going to rise, a lot of jobs and even industries are going to disappear, and the America which comes out of the coming recession will be much changed from the one you’re living in now.