With just a tweet of encouragement from a well-known alternate history writer, I set to work

____________

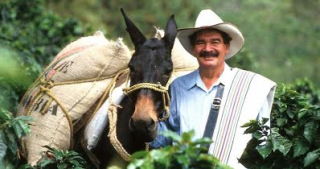

The old man put on his “Juan Valdez” hat, a term his young employees did not understand, and walked slowly into the greenhouse, a sling across his left shoulder, the basket against his right hip.

The delicious fruit, with its precious stones, awaited him. His hands shook in anticipation.

Carefully, he pulled down a branch and picked only the ripest, reddest cherries, placing them one-by-one in the basket. It took him nearly an hour to fill the basket, not due to his age but to his care, for he avoided all the green, unripe fruit that had long been pulled routinely by those desperate for what lay within.

By the time his young workers arrived for work, chattering in a half-dozen languages, the old man was sitting at their shared lunch table, picking fruits from his basket like an aged chimpanzee, stripping off the thin fruit layer with his teeth and gums, then carefully placing each seed beside him in a dish. Satiated, he hefted the remaining fruit in its basket and placed it in the hopper of a processor.

The fruit had an intense, citrusy taste and a grape-like texture. He rubbed his hands together after emptying the basket, then smelled them with pleasure. The fruit not only tasted great, and energized him, but left a waxy residue which made his hands look younger. The fruit would be separated from the stones, dried into a pulp, and become a second harvest for the greenhouse.

His workers would go through the greenhouse today harvesting from several trees, separating the red fruits from the green, and processing them all so that, when the seeds were dried green, then roasted, they could be crushed to create what was now the most expensive beverage in all the world.

Coffee! Glorious coffee!

The wind hit him like a wall. It was negative 4 degrees outside, and it came at 60 kilometers per hour. The old man’s critics wouldn’t understand this, as they still used old English measurements, but the old man knew what it meant. The blizzard was coming. The final blizzard was here.

The old man grunted and strained, alone against the cold. His knees bent, his back protested, and with an agonized sigh he fell forward into the snow.

There he dreamed.

It was the energy of the future, of the glorious 20th century that would make everyone rich and eliminate smog. It had made his father a billionaire, and the old man one too, until he rebelled.

When scientists at UCLA first noticed global cooling, the politicians ignored them. They said,

Yet, even after the Turtledove Machine inventor’s great grandson joined in the protest, they kept using the Turtledove Machine. They kept building more of them. Young activists in England, in West Virginia and even in China tried digging up coal, and burning it, hoping to offset the ignorance of their elders. But this energy cost too much to make, it was non-competitive, the market spoke and their efforts failed. All the world’s infrastructure was geared to the Turtledove Machine. Even when summer afternoon temperatures in Arabia got no higher than 25 Celsius, still they kept buying them. They bought General Turtledove, they bought General Turtledove Motors, they bought shares of Exxon Turtledove with both hands.

But global cooling was real. A heat pump may take energy from a freezing day and use it to warm a bedroom, but there was a price for that. The price must be paid.

So it was that the air cooled, degree by degree.

But no, the experts responded. Look. That Icelandic volcano was fueled by internal fires, and when it erupted, didn’t the temperature go down even faster? Fossil fuels were a chimera, a U-turn on progress, an expensive luxury. They were not a path forward.

The voters believed them.

All this history rushed into the mind of the old man, as he lay in the snow in the heart of the frozen Amazon, which now fell in sheets and covered him over.

It felt good to die. It felt comforting, like a bed with warm flannel sheets and deep, comfy pillows. The old man imagined waking in heaven to a sunny beach, an umbrella drink in his hand, his late wife now youthful beside him.

That night, as the young workers slept and wondered where old Harry Turtledove had gotten to, the dome of the greenhouse cracked, the warm air rushed out, and the last coffee plants in all the world froze to death.