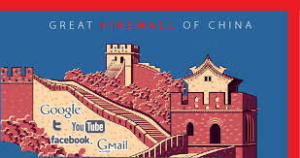

A lot of people like to complain about the lack of online freedom in China.

A lot of people like to complain about the lack of online freedom in China.

It’s true. The government there decides what people can and can’t see, what they can and can’t say. The social conditioning is impressive and made more impressive by the constantly-growing economy.

But if Jack Ma, or anyone in his Alibaba executive team, wants to learn something from the online world, or say something online, it’s not a problem. The same at a thousand other large enterprises. Freedom is doled out with an eye dropper, but for those who need it the firehose is available.

Is the situation better in our country?

That’s what we like to pretend, because government doesn’t censor much of our Web. But it’s still inaccessible, because of private business.

That’s what we like to pretend, because government doesn’t censor much of our Web. But it’s still inaccessible, because of private business.

If a paper puts up a paywall, and you don’t have the money to climb over, or don’t want to spend the money, the information behind that paywall doesn’t exist for you. The only way you’ll learn what was reported is second hand, as when Reuters or Business Insider repeats something from a paywalled paper. And how long before those second-hand links require payment to the first-rights holder? Not long.

Meanwhile, a lot of elites are complaining now about the takeover of our remaining newspapers by vultures who will either tilt them politically, break them up for parts, or both.

Journalism is a business. It’s not a profession, it’s not even a trade. It’s a business, and businesses that don’t have functional business models don’t stay in business.

I have been writing since long before the Web was spun about journalism business models. Mainly I’ve said that journals turn advertisers into business partners. They must create sales for these business partners. There are many ways to do this.

Over 20 years ago I suggested newsletters with coupons that could be tracked was one way. Sponsoring special paid events are another. Insider discussions were a third. The key, in these as well as other cases, is to become ever-more intimate with the needs of your audience, which is what journalism should be about, then use that intimacy to benefit your partners in the market, which is what advertising is about, then ring the cash register.

Instead, when newspapers found that companies no longer wanted to buy billboards alongside their content, preferring more measurable billboards from Google or Facebook, they said, “readers should pay for news” and tossed away 90% of their readership. The fact is that 40 years ago, when I started in this business, we all knew that newspapers only spent 8% of their budgets on the product and collected only the cost of getting that product to readers. The Internet drops that cost to nothing, but newspapers have responded by dropping 90% of their readers, and 90% of their news effort.

Google and Facebook didn’t kill newspapers. The papers committed suicide. Now those two companies, seeing the mess they caused, are trying to “make amends.” On January 14 WordPress rolled out a new Google-backed version of itself called Newspack, designed to help local newspapers create new business models.

Newspack cost about $2.5 million to develop. Google says it has put $300 million into its effort at rebuilding online news. Facebook says it’s kicking in its own $300 million.

There are publishers out there who know how to make money in this new space. Take Josh Marshall, for instance. He founded TalkingPointsMemo in 2000 as a one-page blog, just like the site you’re now on. He has built it into a major news organ covering Washington, while based in New York. It’s free, but there is a paid tier with extra content, discussion threads and events. That means it can maximize its circulation (thus its ad revenue) while at the same time generating income from readers.

If I wrote this a few years ago, I would have first mentioned Vox, and founders Markos Moulitsas and Jerome Armstrong. They came out of the 2004 Howard Dean campaign. Markos still runs Daily Kos, the liberal clubhouse. Vox now owns several national sites with local versions, Eater, Curbed, and SB Nation, as well as tech sites like Recode and the Verge. It has sometimes gotten a little ahead of its financial skis, but it’s still in business after 8 years.

Gannett has an investment in Spirited Media, and if Google wanted to do something specific for the industry it would buy that investment and re-sell it, because if Alden Capital buys Gannett, as now seems likely, that old-line company too will be broken up.

The point is that handing money to existing news industry failures, or to journalistic trade groups, is a huge waste of time. The people who haven’t figured out their opportunities in 25 years aren’t going to magically figure them out because someone bigger writes them a check.

Journalism is a business that is desperately in need of entrepreneurs. Google, Facebook and Amazon.Com won’t have their political needs met by a media that depends entirely on charity and political patronage for its survival. Objective, provable truth needs to have a dominant place in the nation if democracy is to survive this crucial period.

Instead, invest in entrepreneurs. Require that every kid in journalism school take business courses. Talk to entrepreneurs, not writers. Create publishers, not editors.

We need journalistic entrepreneurs today, dedicated to the free web, even more than we need politicians and groups dedicated to beating Trump. You can’t guarantee the second without the first. You can’t beat the lies unless the truth is available to everyone.

Otherwise our Web might as well be China’s.