This is one in a series of short stories I've been writing during my own coronavirus quarantine. You can find the complete collection of fiction written especially for this blog here. My books are available on the Amazon Kindle, for sale or for reading via Kindle Unlimited.

__________

He was born Frank White in Newnan, Georgia. But he became known around the state, and wanted to be known around the world, as Lem LeBlanc.

He was born Frank White in Newnan, Georgia. But he became known around the state, and wanted to be known around the world, as Lem LeBlanc.

Lem grew up in the “Age of Emeril,” the golden days of the 1990s when he would sit at home with his mother and watch FoodTV. His father had left before he was born, so he never took the man’s last name. The home belonged to his mother’s parents.

Lem wanted desperately to follow his hero’s path. That’s why, when he got into Johnson & Wales (the Charlotte campus, not the one in Providence Emeril had gone to, but he didn’t know that) he changed his name. LeBlanc sounded like Lagasse, but he couldn’t be Emeril (that would be silly), so he was Lemuel.

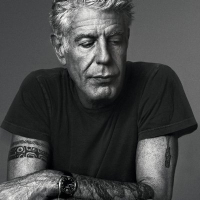

By the time he finished in 2005, chefs around the country were becoming established stars. But there was a new style coming along. It was a search for “the good stuff,” for authentic foreign flavors, pioneered by an ordinary sous chef named Anthony Bourdain.

The good stuff held local or regional provenance. The good stuff took poor, local ingredients and made magic with them. The good stuff wasn’t American cooking. So instead of seeking a four-star restaurant or resort gig, Lem LeBlanc sought to travel the world.

Lem was a willing student. He just wasn’t a good one. What he produced in his few off-hours, on Monday or Tuesday nights, was a pale imitation of the tastes he craved. When he measured his costs, as he’d been taught, he saw there was no profit in it for him.

So, Lem began looking for another way in. In the 2010s he found it in Guy Fieri.

Fieri was all show and all American. Fieri had won his gig on a FoodTV reality show, and what he became famous for was wandering the country watching other people make gut bombs. He tasted sandwiches you’d need to unhinge your jaw to eat. He laughed with fry cooks and pit bosses. He pretended that everyone else around him was a star, and that made him a star.

Lem decided to be a star.

Conventioneers from around the country flocked to Lem’s to get their favorites, and diss those of other diners. Every few months he would debut some new sausage he’d learned about. He opened for breakfast and served German Weisswurst, a white veal sausage you could suck out of its casing. He did Icelandic dogs, he did Argentine Choripan, and Brazil’s Cachorra-Quente. He got $15 for his dogs, with $6 beer and a 25% tip.

It was a gold mine.

In 2016 Lem opened a burger joint, serving a version of Linton Hopkins’ Holeman & Finch burger (you can’t copyright a burger recipe). He used Wagyu beef, cooked on fiery grills in a glassed-in kitchen in Dunwoody, at a $50/diner price tag. In 2018 he opened a pizza joint, just like his hot dog stand, by the new Braves’ Stadium in Marietta. It did New York pies, Chicago pies, and turned out authentic Italian pies you could eat with a knife and fork.

Lem was like Amazon.Com, measuring his success with cash flow, plowing every dollar that came in back into his business. His proudest moment came in late 2019, when Guy Fieri himself came up to the hot dog joint, and Lem personally pulled a collection of dogs off the line, all carefully prepared by his staff, to stuff the host and laugh with him.

Then came Covid.

Lem tried to adjust. He tried to offer delivery, but the delivery services forced him into a loss. When people got his burgers and dogs delivered, they realized these were just burgers and dogs. Without the atmosphere of the restaurants, without the hubbub and the crowd, the prices looked outrageous.

Lem laid off half his staff. Then he laid off half the rest. He refused to pay his rent for May. His landlords fetched the health inspectors, who closed him down by Memorial Day.

Lem LeBlanc was Icarus. He’d flown too close to the Sun. The age of the celebrity chef was over. Bourdain was dead.

Lem moved back in with his mother in Newnan. He was a 40-year old man living with his mom, mowing her lawn on the weekends. He told friends it was her health. But she was still just 60. She was a nursing administrator at Piedmont Newnan hospital. She made good money, did yoga twice a week. She had made a great life for herself and, while she took her boy back, there was a niggling resentment she couldn’t hide.

Lem drank.

Lem was a solitary drinker. He started with a beer or two after doing the yard. Then he started experimenting with cocktails. Then he started going through bottles. Then the bottles got cheap.

Over Christmas, in 2022, Frank White was kicked out of the house by his mother. (He had never put up the money to make Lem LeBlanc his legal name.) She demanded he find a program, an AA meeting. She said it was for his own good. She wasn’t going to enable his addiction. She had been secretly practicing the speech for months.

He was on the street. After one last blowout, under a freeway viaduct in Atlanta’s West End, he woke up bleary-eyed, without money or ID, and with gangrene eating the pinky toe on his left foot.

He had hit bottom. He finally took mother’s speech to heart. He did love his momma.

“My name is Frank, and I’m an alcoholic,” he said at his first meeting. Then, a few weeks later, “My name is Lem LeBlanc, and I’m an alcoholic.”

His comeback had begun.

But word got out. That summer a man named Gordon Muir called the house in Newnan. Ann had taken her son back in after he dried out. Muir offered Frank White a job. It was a starting position, but he was going to retire himself someday, and he needed management material. He said Lem had been a manager. He might become a manager again.

So it was that, one fine spring day, Lem LeBlanc drove an old Toyota Scion up I-85 to the North Avenue exit, parked on the bottom of a parking deck, in the shade, and put on a red-and-white paper hat. He laid out his best smile for the customer in front of him and asked the magic Atlanta question.

“What’ll ya’ have?”

Lem LeBlanc had joined The Varsity.