This is one in a series of short stories I've been writing during my own coronavirus quarantine. You can find the complete collection of fiction written especially for this blog here. My books are available on the Amazon Kindle, for sale or for reading via Kindle Unlimited.

__________

Buck Frederickson was approaching 70 as the year 2020 opened, but he still went to the shop every day. Buck’s Appliances in St. Cloud helped Buck’s son, Chuck, become the first Frederickson to graduate college, in 1990. Chuck became a State Farm agent and earned enough, in turn, to pay all Jake’s bills when he went to the U in 2018.

Jake wanted out. He had a vague major in the sciences. He wanted to do something relevant.

While Chuck was more into Prairie Home Companion than Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and cursed the day Garrison Keillor was forced out by the “me-too” movement, the old rock songs became his son’s anthems, as they had been his father’s.

Buck’s defiance was what Jake wanted to follow.

When the pandemic came and the school closed, the car moved with Jake down to 26th Ave. There was a Target nearby, and he picked up phone orders in the parking lot. Jake mastered the online syllabus and got his best grades ever.

Then it happened.

Jake was tempted to join but he was a biology major. He knew that droplets from spitting or even breathing could spread the disease, and that the disease could kill. COVID-19 mostly killed older people. Jake knew it could also kill him.

Stay inside, Chuck said, and Jake was tempted to join the demonstrators. Stay inside, Buck said, and Jake stayed inside.

There were blackouts regularly now, and the small air conditioner on his window went out. He couldn’t very well go grab the WiFi at Tim Horton’s on E. Lake. Everything was closed.

“I didn’t want to worry you,” said Chuck.

But Buck had the virus. He hadn’t been tested, but he believed he had it, and Chuck acted like it was true.

Still, Buck refused to go to the hospital. Buck said only sick people went to hospitals, and they did that to die. Let younger people have the beds, he said when Chuck pressed him on it. The arguments were contradictory, but Buck would not be moved.

Chuck laid in a stock of gowns, masks, and gloves. Jake’s mother, Carla, was at Buck’s home, tending to her father-in-law.

“You belong on campus,” said Chuck when Jake got home.

“There is no campus,” said Jake. “Can I see grandpa?”

Chuck nodded, yes.

Jake drove to his grandpa’s little house. It was identical to the place he lived behind, on 26th St. It was tiny, just 1,000 square feet, but there was plenty of space to park on the street.

“The neighbors don’t know,” Chuck had warned his son, so Jake didn’t bring flowers. He just knocked on the side door, the one that opened to the kitchen through the mud room, and Carla answered.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Jake asked.

“Didn’t want to worry you,” Carla said. This is the Minnesota answer to every hard question.

“How is he?”

“He’s not on a ventilator,” she said, “but lately his breathing has become difficult. I’m glad you’re here. He asked for you. Outfit yourself.” She pointed weakly toward the home’s small living room, where there were piles of PPE – swabs, gowns, masks, gloves. Near the door was a large Hefty bag. The used gear was to be tossed in there.

“How did you get this stuff?” Jake asked.

“This is amazing,” Jake said. As he finished tying the face guard, he heard his grandfather’s cough, weak and hacking. He knew from his reading that the virus’ clotting was especially acute in the lungs, and that once they were too weak to work without a ventilator death was likely. A tear fell along one cheek, but he couldn’t wipe it away.

Instead, Jake walked down the short hallway and appeared in Buck’s bedroom. Carla had propped her father in law on enough pillows to choke a St. Bernard.

“Hey, gramps,” said Jake.

Buck stopped coughing long enough to see who was behind the second mask and gown. “Jake,” he wheezed, and tried to smile.

“You heard about what’s going on back at school,” said Jake. Buck motioned weakly to the flat screen TV propped on a bureau opposite him.

“I saw,” he said.

“You were in it,” said Jake. “You were part of it. The 60s. They’re back, gramps. I need to know what to do. What did you do?”

“I saw,” Buck said again. Once more he pointed toward the TV.

“I don’t understand,” said Jake.

Carla filled him in. “Jake, your grandfather never went to any of those demonstrations. He got a high draft number. He never left St. Cloud. He just watched it all on the TV.

“He was my hero,” Jake cried. “He said he did all that.”

“He saw all that,” said Carla. “He witnessed all of that, right here in St. Cloud. It made him what he became.”

“But he never marched,” said Jake. “He never faced the cops. He never did any of it.” He looked back at his grandfather, and the look in his eyes sent Buck into another coughing spell. A long one this time.

A fatal one.

A few days later, with his grandfather in the ground and the store doing its going-out-of-business sale, Chuck and Carla greeting customers like the family at a wake, Jake raced home.

He parked his car on 26th Street and then he took a walk. He went to E. Lake, then he took a right. He was determined to finally be a part of it, to be more than a witness, to do something for the cause of his time, and to make black lives matter.

But he was too late. The police were gone. The demonstrators were gone. Instead of the acrid smell of smoke, there was the smell of flowers. The place where Floyd had died had become a memorial. Instead of seeing riot police he saw one community relations officer, standing without a gun, without even a club. It was a black officer. When people approached, he hugged them, listened to them, cried with them.

Maybe, he thought. But no more.

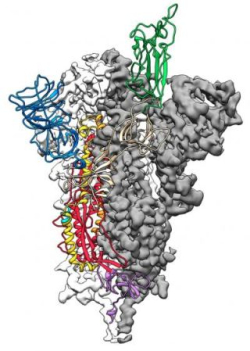

He would become a virologist. He would join a lab in the school’s vast biological complex. He would find ways to fight coronaviruses of all kinds. He would turn down money from the big drug companies, and he would stay on 26th Street, buying the house his garage apartment sat behind.

And he would vote.