This is one in a series of short stories I've been writing during my own coronavirus quarantine. You can find the complete collection of fiction written especially for this blog here. My books are available on the Amazon Kindle, for sale or for reading via Kindle Unlimited.

__________

The deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history, in Las Vegas, Nevada, killed 58 people.

The deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history, in Las Vegas, Nevada, killed 58 people.

Larry Murray, known as Murray the Spreader among the regulars at Biloxi’s Beau Rivage casino, where he was a dealer, felt certain he could beat that.

He also thought he could get away with it.

When the Beau Rivage re-opened in early June, he was ready. The company had protocols in place to check temperatures and separate gamblers, but Larry Murray was confident these were garbage. Besides, they couldn't police his off hours.

He knew it was only a matter of time before he got the virus.

Murray was 32. His parents had been snowbirds, who moved from Missouri to The Villages in Florida as soon as they turned 55. That year he was graduating from the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, with a 2.0 average in economics. He added a certificate in casino management that summer, then took I-59 south.

Murray was 32. His parents had been snowbirds, who moved from Missouri to The Villages in Florida as soon as they turned 55. That year he was graduating from the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, with a 2.0 average in economics. He added a certificate in casino management that summer, then took I-59 south.

For the next 10 years Larry Murray went from house to house, from Harrah’s in New Orleans to the Island View, Scarlet Pearl, and the Hard Rock on the coast. The Beau Rivage was his big score. It was a huge casino that could hold thousands of gamblers and, when he held forth at his blackjack table, or dealt poker in a private room, Larry Murray was the center of attention. That was all he wanted to be.

That’s where he got his nickname, from the way he fanned out the cards and spread joy even among his losers. It had nothing to do with what came after.

Larry hit the jackpot on June 18. It was on one of the casino’s regular tests, too, not one of the homegrown ones. It was a free ticket. The supervisor who gave him the news was terribly sad.

Larry was thrilled beyond belief.

Almost before the words “I’m sorry” were out of the supe’s mouth, Larry Murray had pulled up Expedia on his iPhone. He needed to get out of town fast, and now he didn’t need to worry about the risk, because he’d already gotten his snake eyes.

Larry sat on both planes, without a mask, and as soon as he landed, he grabbed a cab for the arena. He joined the crowd outside, bought himself a MAGA hat and, when it was obvious there wasn’t a full house, pushed his way in.

He wandered the hallways, shouting, shaking hands, waving an American flag. Hardly anyone in the place cared about the risk. They thought the Man would protect them. Larry knew better but didn’t let on.

This was just step one in his plan.

Realizing he had to work fast, Larry used his Beau Rivage ID to get on as many gaming floors as he could, all crowded with drunks and other patrons of the dark mathematical arts. He wandered up and down Las Vegas Blvd., his energy seemingly inexhaustible, and finally took a room at Circus Circus. He slept for just four hours, cabbed to an open breakfast place on Decatur St., then returned to the action. He played a few hands, but the casinos were being careful. He was much better off meeting people, sharing drinks, slapping backs, and just breathing, laughing when he sneezed, wiping his snot off on drunk women who thought it was funny.

Two days later Larry decided to rent a car. He drove into Death Valley, to Zabriskie Point, and started getting thirsty. He bought something at a roadside stand, and he started getting hot.

By the time the sun set outside Carson City, Larry was feeling mighty poor. He drove to the emergency room at Carson City Tahoe Medical Center, parked out front like a partner, and hauled himself in to be checked out.

The duty nurse knew just what she was looking at. She’d seen it too many times. She hollered for a gurney. She didn’t touch the patient, didn’t get near him. She threw a mask on him, and gloves, and a face shield, so that he wouldn’t infect others, and sent him directly to the COVID ward.

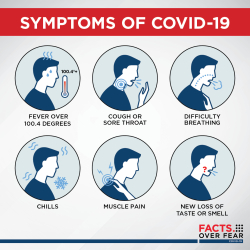

Despite his youth, Larry had it bad. He had no idea that blood type A made him susceptible. He had no idea he had incipient diabetes, and hypertension. Not at his age.

The next few days were touch and go.

Larry couldn’t talk to anyone until a week later, when they took the ventilator out and put him in a general ward. He still felt like hot garbage but at least now he could breathe through an oxygen tube, keep some toast down, and water sure tasted good.

They started to talk, and she asked Larry where he’d been before he got sick. The girl’s name was Molly Smith, she was a cutie, so Larry told her the whole story. He described the sights and sounds of Las Vegas, the excitement of the Trump rally, and every airplane he’d been on from New Orleans. He had a photographic memory, from dealing cards he said.

Molly took it all down, nodded carefully, giggled in the right spots, and leaned in close when his voice faltered. When he was finished, Larry said he was tired. Molly said she would let him rest.

Then she rushed upstairs, to the hospital’s administrative offices, and shared his story with them.

The administration was horrified. The chief medical officer called a friend at a Reno TV station to slip her the exclusive. Then he got to work on the Web, tracing Larry’s steps, measuring them against a database of cases.

The reporter who came to the hospital was the administrator’s niece, a sister in law’s kid from her second marriage.

Larry Murray made Ann Newsome’s career.

Over the next two weeks, as the news went up the line, and the contact tracing intensified, it was discovered that Larry Murray had infected over 2,000 people of which, over the next few weeks, 58 died.

Murray himself took a turn for the worse and passed on the 8th of July.

But while his death was terribly painful, Murray had something he could take away from it.

His death was number 59 attributed to his spree. People would argue long and loud over the succeeding days whether his death should count, because he was in effect the shooter and you don’t count shooter deaths in mass shootings.

But on the 11th Molly Smith died, and Larry had the record all to himself.