My Congressman died last week.

My Congressman died last week.

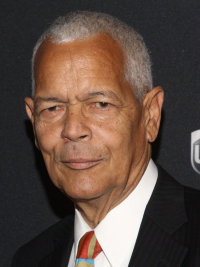

John Lewis wasn’t built to be an executive. He was a legislator, the conscience of his time. He absorbed the blows and lived to become an icon.

John Lewis believed in “Good Trouble.” He practiced it, for longer than any other American, 60 years. In time, that’s the distance between Thomas Jefferson’s election and that of Abraham Lincoln. It’s the distance between Theodore Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy. From lunch counters, to city streets, to the U.S. Capitol, John Lewis never let up.

Good trouble means pushing people in power to do more, being a pest even to your allies. It means confronting evil, standing for what’s right. It means being unafraid, in the way Gandhi was unafraid, in the way Dr. King was unafraid.

In the way John Lewis was unafraid. Whenever I met him, he was gracious, wise, and conscious of his life’s meaning. He always humbled me.

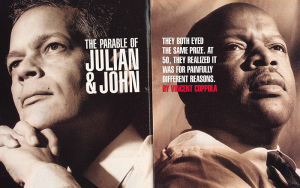

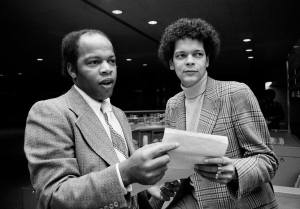

But John Lewis was no plaster saint. When he wanted something, he could be ruthless. This is told in a story I witnessed. While it didn’t make his obituaries, it was featured in that of the man whose career he ruined, Julian Bond.

When I moved to Atlanta, nearly 40 years ago, John Lewis was an Atlanta city councilman. He was an annoyance to Andrew Young, who had succeeded Maynard Jackson as Mayor. Lewis didn’t like the compromises that come with governing, the corruption inherent in hiring people to haul dirt for a runway, or finding a job for some wastrel son or cousin of somebody who could help do the city’s business. Lewis had no patience for any of that.

When I moved to Atlanta, nearly 40 years ago, John Lewis was an Atlanta city councilman. He was an annoyance to Andrew Young, who had succeeded Maynard Jackson as Mayor. Lewis didn’t like the compromises that come with governing, the corruption inherent in hiring people to haul dirt for a runway, or finding a job for some wastrel son or cousin of somebody who could help do the city’s business. Lewis had no patience for any of that.

To the new Atlanta establishment, a failing run for Congress seemed the perfect place to dump him. The 5th is the City of Atlanta district. Its boundaries have, since I have been alive, been defined (pretty much) by the city’s boundaries. When Wyche Fowler decided to run for Senate (a race he won) Lewis was quick to announce.

But he was the underdog. Julian Bond was the legend the city’s politicians wanted in that seat.

Lewis, born in southern Alabama, was dumpy, dark, brooding. When he spoke, he sounded like he had marbles in his mouth. He was the son of a sharecropper. John Lewis wasn’t a wheeler-dealer, either. He had no patience for it. He stood for the moral high ground. The man who looked like a pol wasn’t one, while the man who looked like a magazine cover was one.

Early polls had Bond winning 2-1.

Then Lewis found Bond’s weakness. Drugs were his weakness. His marriage was falling apart. Lewis demanded Bond take a drug test. Bond refused, citing the Fourth Amendment against seizing his blood, the Fifth against self-incrimination.

That fall, I wanted to take my dear wife to a big Amnesty International concert in the Omni, long since torn down. It was a tough ticket. The line-up was incredible. South Africa was the issue. Bond was big on South Africa. When I went to a CD store to get tickets, I was told they were unavailable. But I saw a few. They were sitting next to the salesman’s shoulder. They’re floor seats, he said. I want them, I said. The clerk warned, they’re right behind Julian Bond. I said I’d take them anyway.

Sure enough, Bond had bought a whole row. He sat on one end, his wife on the other. We enjoyed the concert, but I also saw a big man right next to Bond, whom I later learned did indeed sell drugs. The final election result was narrow, but Lewis’ whispering campaign worked. He never had a hard race again. But he kept using that 1986 sign, with the aging typeface and the red dot over the i.

Outside the Republicans had ginned up a lot of Tea Party demonstrators. Their aim was to intimidate the House, possibly prevent the vote.

After their meeting, one member suggested the leaders walk a tunnel under Capitol Hill to the chamber, for their safety.

“Let’s go,” said John Lewis. “We’re crossing the street.”

They did. Nancy Pelosi walked with her gavel, John Lewis walked next to her, and the rest of the leadership struggled to keep up. Obamacare passed.

That was good trouble.

Right now, in 2020, we need good trouble more than we ever have before. We need it like we needed it at the Pettus Bridge. We need it like we needed it during the Great Depression, through the Progressive Era, and in the days before the Civil War. We don’t need deal makers and we don’t need pols. We all need to find the John Lewis inside ourselves.

We’re doing it. Trump decided recently that his Gestapo, which goes by the name of the Department of Homeland Security, should occupy Portland, Oregon, hauling people off without cause, putting the whole city under lockdown, forcing demonstrators to surrender. But the people are resisting. They’re showing up in greater numbers than ever before. They’re demonstrating peaceably, drawing the press, giving their oppressors no quarter. They have made their city a Pettus Bridge, and they’re walking.

Evil has never been so prevalent in American politics, but it has also never been so brittle. Stand now, make good trouble, and it will crack. It will break. We will become America again. Hide like that Congressman wanted to do 10 years ago, like the Johnson Administration wanted John Lewis to do, and we can lose this last great hope of Earth. Maybe forever.

Now is the time to take the lesson of John Lewis’ life and apply it wherever we are, to be ruthless in speaking truth to power, in demanding more from ourselves, from our government, and from our fellow citizens.

Now is the time for Good Trouble.