I’ve made a lot of money. The value of my stock portfolio has tripled. I’ve found a good niche with InvestorPlace that has eased me toward retirement. I only work because I want to. Social Security would pay me more right now. But writing isn’t a job. It’s living, it’s breathing. If you can get paid for it, that means people are reading you and benefitting from it.

I’m very, very fortunate.

Most of my last decade has been spent following the clouds. Cloud computing, which combines distributed processing, virtualization, open source, and scale, has proven itself as the 21st century’s first great technology revolution.

Instead companies that never took a dime from the government, like Amazon, Google, and Facebook, now dominate global telecommunications. The phone network is dead and cable networks are dying. Billions of new people can now be part of the global conversation.

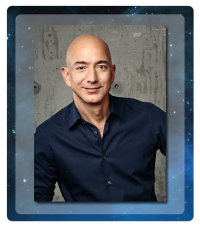

As I write this 5 companies – Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Facebook – have a combined market cap of nearly $7 trillion. Apple alone is worth $2 trillion. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is worth $200 billion. Anyone who invested money in this transformation has grown wealthy. Hard as it is for me to believe, I’m a millionaire.

But a hard rain must fall.

What we do know is this. Money no longer comes out of the ground. It rains down from the clouds. At the end of August Salesforce.com, born to provide Oracle databases as a service in 1999, replaced Exxon Mobil in the Dow 30. Note that Oracle, which fought open source for a decade, then denied the economics of the cloud, didn’t get in. Salesforce passed it in market cap a few months ago.

One thing the cloud did without Wall Street recognizing it was to make stock assets liquid. You can now trade stocks free. In just a few clicks, you can buy or sell any public company. Stocks are, as an asset class, nearly as liquid as cash.

But stocks aren’t cash. Every dollar is worth a dollar. But a stock is only worth what the last person paid for it. If every Amazon.Com owner rushed to the rail and sold tomorrow, they wouldn’t come out with $1.6 trillion. They’d get a fraction of that. We saw this as recently as March, when trillions of dollars in value disappeared in a pandemic panic.

One of two things is going to happen, very soon.

First, the economy may not come back, meaning the cloud stocks must fall.

Alternatively, the economy may come back, meaning the cloud stocks must fall. If the airlines show signs of getting through this, people will want to own them. The same with cruise lines and hotels. The money needed to invest in these new opportunities must come from somewhere. Why pay 40 times earnings for Google when you can double your money on Delta in a few months?

Cloud stocks are valuable, but they’re not worth what people are paying for them. Fundamentally, even the shares of fast-growing companies should be worth no more than 25 times earnings. Amazon and Nvidia sell for 100 times earnings. Over time, fundamentals apply.

So, it’s time to look at undervalued stocks, even if it means I’m not getting fat gains. I bought some Bank of America recently, and some Intel. I will do more of that, taking smaller gains for greater safety.

That’s the one thing I’ve learned in covering finance. Risk never disappears. You’re never really on solid ground. Fashions change, and you can’t fall in love with your stocks. As Pete Townsend wrote when I began this gig, the music must change.