Once you show you like something, I offer you more of it.

Once you show you like something, I offer you more of it.

Is this a conspiracy?

Not unless I’m a scaled Web site. Because this is at the heart of the charge against “Big Tech,” the companies I call Cloud Czars.

- Show a preference for certain videos on YouTube and YouTube offers you more videos like them.

- “Like” things on Facebook or Instagram, and you will get more things like them.

- Follow certain celebrities on Twitter, you’re offered more like them.

- The same with Amazon Kindle books. When you buy something from Amazon, you’ll be followed for days by ads offering the same thing.

The algorithms follow human nature. Chances are that if you like a book about 12th century monks who solve murders, you might like another one. If you like Henry Winkler, you’ll probably like Ron Howard.

The problem is that if you like crazy conspiracy theories on Instagram, or videos describing the terrors of the Illuminati on YouTube, you’ll get more of them. Like those, you’ll get more. And more and more.

What the critics object to is the collection of this preference data, then its use. These critics demand privacy. Which you can get. In which case the web sites become less useful.

I can’t serve you unless I know about you. The first time you go into a restaurant you’ll get bland, one-size-fits-all service. The 10th time they’ll anticipate your needs. The 20th time they’ll call you by name. You’ll enjoy it. It will become your favorite place.

All the Czars are doing is what the restaurant does. They’re also doing it for the same reason, to make you a happier customer. To anticipate your needs and desires. To serve you better.

Hillary doesn’t eat babies. The e-mail fantasy is just that. But if you believe the e-mail fantasy, you might buy the one about eating the babies.

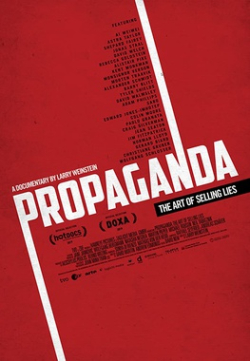

People naturally tend to go down rabbit holes. Marketers take advantage of this to sell us things. Politicians take advantage of this to gain power over us. They use one lie, then another, then another, and pretty sure you’re so far down the rabbit hole that truth can’t reach you.

For people who feel threatened, it’s a tactic as old as time. It was used to create the Confederacy. It was used to create Hitler. It was used by ISIS. It’s being used by Trump.

Breaking it is simple. Make the first liar responsible for the lies they tell. They’re going to claim First Amendment protection, but that’s a red herring. Colgate can’t put out bad toothpaste and call it whitening. Society has an inherent right to protect itself.

A 19th century theater was a dangerous place. Limelight involved burning harsh chemicals, and an accident could bring disaster. That’s where the concept of not shouting fire in a crowded theater comes from. It’s also where asbestos curtains came from.

The point is that the problems we perceive with “Big Tech” aren’t tech problems. They’re human problems. We need to treat them as such. These problems exist in our markets, and in our politics. They stop when we call out the liars and make them pay for the lies. They stop when we stop giving them oxygen, when we stop taking their ads, when we jail them for incitement when they incite violence.

This was easy to do when terrorism was coming from Middle Eastern mullahs. It’s not so easy when it’s coming from inside the house.