A few years ago, when I started writing for InvestorPlace, lots of stocks offered fat dividends. Yields of 3% were not uncommon. With interest rates near 2%, it was a bargain.

A few years ago, when I started writing for InvestorPlace, lots of stocks offered fat dividends. Yields of 3% were not uncommon. With interest rates near 2%, it was a bargain.

Today dividends are rare, and low. This doesn’t mean companies have found better things to do with shareholders’ money.

It means they read the tax laws.

Under current tax law dividends come out of a company’s net income, which means they’re subject to corporate income tax. Then they’re part of the recipients’ net income, where they’re also subject to tax. Critics like to say they’re taxed twice.

If the same company takes the same money and buys back its stock, as Google is now buying back $70 billion of its stock, it’s not income to the recipients. But if it raises the value of Google by just 3%, it has the same effect. And it’s likely to do just that. The benefit also comes to shareholders as capital gains, which is taxed at a lower rate than dividend income.

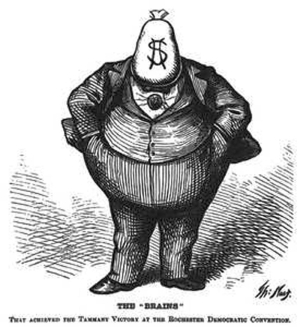

There’s another reason to do this. Many top management contracts are tied to increasing a stock’s value. If the stock goes up because of buybacks, management collects. That collection may be in the form of stock, which is why a lot of buybacks don’t reduce the number of shares outstanding. The company hands out stock and options to managers, the buyouts maintain the price of the stock, and the managers collect more stock.

Stockholders aren’t benefitting from stock buybacks nearly as much as managers and other insiders. It’s a situation ripe for reform.