In the car-bike debate, that’s not always recognized. Advocates treat cars and bikes as a binary choice. But in the electric age we are now entering they aren’t, and they won’t be.

How you get around should be scaled to your needs and desires, not your budget. Electricity makes this possible, because electric motors scale. It’s the job of urban planners to accommodate all our choices.

There will be many.

I get that not everyone likes to pedal. Some people travel long distances and need speed, while others travel short distances and need safety.

Computers are also taking over traveling clients. There are now electric wheelchairs that can go 15 miles an hour, with motors that can lift patients to standing or horizontal, even negotiate a crowded downtown and get up ramps easily.

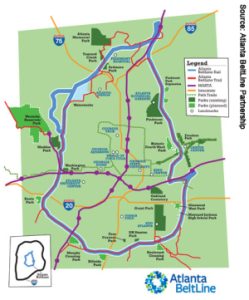

In the next years you’ll see wheelchairs on the Atlanta Beltline. You’re already seeing electric skateboards, some with one wheel and some with four. Electric mopeds that can go 30 miles an hour using just a throttle want on the Beltline, too. Vehicles can scale to the load they’re carrying whether it’s with one person, two, or a whole crowd.

What if the whole city were like the Beltline?

Clients and Systems and People, Too

We have tools to deal with diversity if we choose to. Right now, Americans choose not to.

We should have what I believe Utrecht has, imperfect efforts at regulation, complex rules, subject to change, on who goes where and how fast, aimed at matching the speed of transport to the reaction times of people who are constantly changing their minds. Those 30 mph electric mopeds? You need a license for them in the Netherlands.

The Atlanta Beltline is already a terrible place to ride a bike, with kids and dogs, walkers and wheels, all vying for the same narrow path. The best speed I can do on the east side trail is 10-12 mph. I double that on the city streets I use to get to and from it.

It’s amazing there aren’t more bikes running into people, kids getting hit by scooters, dogs getting tangled up in bike accidents. There aren’t, because the human mind can adapt to the environment so amazingly well.

Take that, AI.

Scaling the Beltline to the Roads

Here’s an inconvenient truth. Hit something at 20 mph or less and you will usually survive. At faster speeds, you won’t.

Yet accidents at speed are common because people oppose any control technology. Car drivers also change our minds. We routinely jump across multiple lanes of traffic when we recognize our exit, make right turns from left lanes. We run over street signs and bicycles every day.

That’s why drivers feel it’s their right to go as fast as they want, even in school zones. There will be a big effort in my state of Georgia, starting next week, to eliminate school zone speed cameras, drivers calling them a “cash grab.” They offer no alternative for saving kids’ lives.

We can create 20 mph cities. We can enforce traffic laws and create safety with technology at higher speeds. What will drive American civilization under in the next decades will be if we resist both.