When people during World War II imagined the world of 50 years previous (and Hollywood films of the time show you that many did), it was the physical changes that stood out. The entire infrastructure of American life was designed in their lifetimes. This was the Utility Age, when phone, electric, natural gas, and transit networks were all built out, with railroads taking people between cities.

The following 25 years saw the most profound changes. Freeways and highways, meant to reduce congestion, took people 25 miles and more from the cities where they worked. The suburbs, where I and most people my age grew up, had arrived.

Looking back 50 years from today, suburbs remain our world. Most changes are internal, from the Apple II to the Apple iPhone, from ARPANet to the global Internet, from Microsoft BASIC to ChatGPT.

I have covered all of it, looking around corners, talking to entrepreneurs who made big mistakes. I saw home shopping, social networking, and mapping applications in the 1980s. I remember seeing an editor with a T-1 line, looking at a Netscape browser, and telling his staff he “had fire,” that he had seen the future.

My point is that computing hasn’t changed how cities work. But electric bikes, and the small mobility arising from them, can change it profoundly.

A short e-bike ride this week brought it home to me.

Alternate Routes

Just two miles from my home, however, the road network becomes suburban. Main streets are separated by a half mile or more. They carry big traffic loads, they have high speed limits, and they’re extremely unfriendly to slow-moving bicycles. I can easily get my e-bike up to 20 mph, and I’ve gone 35 mph downhill, but even at my top speed sports cars and pick-ups (many trailing trailers filled with gas-powered lawn equipment) blow right by me, and I feel like a crazy person.

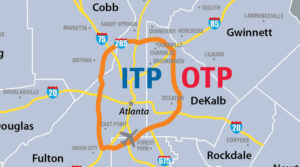

This suburban design is now coming into town, as developers build out big lots into apartments and townhouse projects.

You can’t bicycle between any of these new developments without using what amounts to a suburban highway. Yet a single bike track, just 10 feet wide, could connect the developments with adjacent neighborhoods, turning suburbs into a city again.

The problem is that intown developers build along the existing highway grid. They wind up developing neighborhoods for the 1950s. They don’t see the 2050s, and its more diverse transit mix.

Changing History

Having just one path through town, every half mile or further, with some traffic barreling through at 60 and others going at 15 or even walking speed, won’t scale. Breaking through subdivisions with 10-foot wide bike paths would be a natural solution.

Now let the trolling begin.