The prepositions are to, through, and around. These describe the three aims of transport. We are going to a place, through a place, or around a place.

Before the 20th century, we went in and went out, and going around was unusual. Vehicles went slowly into city centers. Moving within them was also done slowly and carefully. There were people on foot, people in streetcars, people behind horses, on wagons and, eventually, people bypassing the whole parade with subways. You carried whatever you needed. If you needed to move more than what you could carry, you acknowledged the cost and kept to the street’s pace.

The fast car created the second proposition, the desire to keep on driving through a city, and to go around it.

Moses vs. Jacobs

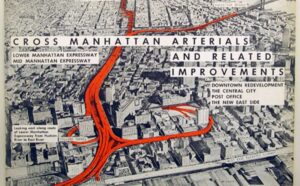

The battle over the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) in the early 1960s was seen, at the time, as a battle between the past and the future.

It was, but the reporters and the power brokers got the two sides wrong. That’s because while Moses, who built two giant freeways to the sky once his Expressway plan was thwarted, did represent the 20th century, it was Jacobs who was the futurist.

I see this every day as I cruise with my e-bike through the east side of Atlanta. The east side has a grid, a 19th century design of thin streets delivering alternate ways to get where you’re going. The grid also creates neighborhoods. It puts life on the street, shops and restaurants, bars and neighbors and parks, creating a fabric that makes life worth living, one that can scale beyond a single story.

The Moses city, which we call the suburb, is sterile by comparison. Its prepositions are through and around. People go through the suburb to get to the next suburb, and the next and the next. Grids don’t exist in the suburbs, only routes leading to giant shopping centers and residential cul de sacs filled with strangers.

Without huge amounts of income to sustain it, not just its people but its infrastructure and the cars, a suburb becomes a slum.

Suburbs Into Slums

You can see this on Memorial Drive, southeast of the city, which is five miles of slum from I-285 east until you reach the “viable,” albeit sterile, upper middle-class suburbs. The same thing happens near Norcross, on the northeast side, Smyrna on the northwest side (called Vinings where it’s gentrified) and Austell due west. Without gentry, a suburb is a sterile slum.

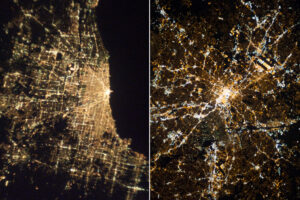

The first decades of this century saw an explosion of development inward. Atlanta changed from a suburb into a city, with four-story high apartments and 40 story high offices. This was centered around Georgia Tech, a new downtown built on the grid along Spring Street. The I -75-I-85 connector, originally built to go through the city, became its ingress. (Don’t use it unless you’re staying a while. Always use I-285.)

The suburban transport system doesn’t scale upward in the 21st century Sunbelt. We’re back to the arguments between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs, between in and through. It’s happening in dozens of different places, not just Atlanta but Houston and Dallas, Los Angeles and Seattle. At some point the place you go through becomes the place you go to, and the only scaled solutions in “to” places are slow and multi-modal, people conscious of one another. Running your living room through a city at 60 mph isn’t just impractical but deadly.

Battle Lines

It’s called the war against cars. It’s really a war for scaled, multi-modal transport, a world where we’re safe even when we’re not surrounded by two tons of steel, where we can stop, and where parking scales because bikes let it do that.

Change is possible because electric motors and batteries let you scale quiet transportation, from the wheelchair and skateboard, through the bicycle and moped, to the car, bus, and train. Electricity offers alternatives to the rolling living room. It makes the “to” places livable. They can be quieter and smell better without all those gas engines. We can get close again.

Electric motors will humanize our cities because the market is demanding them. People are tired of paying the $10,000/year “tax” of owning a car, of insuring it, and of gassing it up so that car can spend 10% of its time on the road going through and around. They want ordered liberty, not your drivers’ license. They demand the right to go to, and to stay a while.