In Atlanta, where I live, this point was reached right after the 1996 Olympics. There was an “explosion inward,” thousands of young and youngish people ignoring the crime fear of their elders, creating “gentrified” neighborhoods. Once these properties grew in value, the neighborhoods filled with prosperous homeowners, the move toward density began. It started within blocks of the center, factories converted to lofts, lofts becoming apartments reaching for the sky.

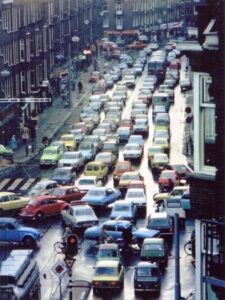

Distance shrank in the new Atlanta. Car travel can’t scale. The average car is at least 6 feet wide by 10 feet long. In the 21st century, many are even longer. Add to that any safe braking distance and you see the problem. Not enough room on the roads.

Technology makes density more attractive. Working from home, buying from Amazon, using telemedicine and ordering Uber Eats, make for less travel. But the 15-minute city, with everything you need within walking distance, doesn’t yet exist in the Sunbelt. Fortunately, we have the 30-minute city, a world where all the things you need are within a 5-mile bike ride, and where electricity makes that 5-mile ride comfortable.

Accommodation to Acceptance

It’s a growing constituency and despite complaints about a “war on cars,” it’s going to keep growing. Change is coming to Atlanta, in the form of dedicated bike lanes, separated from the road by cement lane dividers and, in some cases, paint.

Due to a family issue, I was forced to drive to San Antonio this week, and I brought an e-bike with me. San Antonio is flatter than Atlanta, and near its center it’s a wonderful place to ride. I have done it, and I loved it. But we were further out, near I-410.

Here there is no accommodation to bicycles, e or otherwise, because the “explosion inward” has not occurred. The city is an enormous suburb, running off in every direction, everyone a half-hour drive from anywhere. Even those with modest incomes are forced to buy cars, usually used, often with high mileage and enormous repair bills they can’t escape from. “Anglos” with ancestors from northern Europe, have enough money for nice cars. They think nothing of the distances, even joke about them, as they drive their living rooms and offices in from Boerne or Seguin, filling I-35 to Austin until a toll road was built to Luling, about 30 miles east of the city. This will let them stretch their single-family lot lifestyle alongside US 290 an I-10, eventually all the way to Houston.

No Accommodation

It turned out to be anything but. The “bike route” that Google Maps suggested ran along a 5-lane road under a cloverleaf freeway exit, cars speeding into me from the right as they left the freeway, pushing me from the left as they tried to get on.

It didn’t get better. The only way forward was on a 4-lane road, without sidewalks, with a speed limit of about 40 that no one obeyed, without even marked lanes. The suggested alternates were even wider roads. At one

Absent the explosion inward, San Antonio inside I-410 has grown poor. People can still buy homes, but they’re tiny, old, falling apart, and often surrounded by rusting cars, garbage, and mud. The roads are lined with gas stations, convenience stores, and some of the best Mexican American hole in the wall restaurants in the world.

The point is that San Antonio, and many other American “cities,” remain suburbs. Technology jobs are causing some cities this size, like Austin, to become more diverse, more accepting to bikes within designated areas. But from where I sit now, my e-bike charging in my hotel room, the revolution is a long way off.